How to Isolate a Patient With Shingles: The Two Questions You Need To Ask

Roughly one third of the U.S. population will experience shingles in their lifetime. Shingles can occur anywhere on the body.

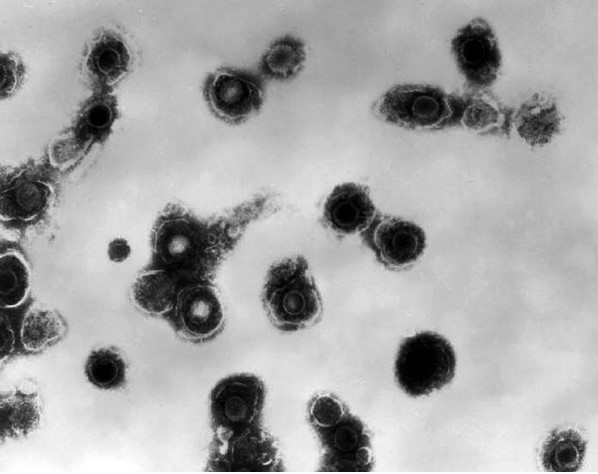

It’s important to recognize shingles so you can protect yourself from exposure. Because shingles is a reactivation of varicella zoster virus (VZV) from having had chickenpox, a non-immune health worker exposed to VZV from infected vesicular fluid is at risk for developing chickenpox.

Whether you call it shingles, herpes zoster, or just zoster, have a process for determining which isolation or transmission-based precautions (TBP) your patient requires — if required at all. It will be an asset to you and your colleagues.

TBP for shingles is not one-size-fits-all like it is for chickenpox. There’s a good chance the patient won’t even need TBP. But it takes some information gathering to make the right call.

Let’s explore the two questions you need to ask so you can feel confident making the decision to isolate or not isolate.

1. What’s the Dermatomal Distribution of the Rash?

Localized Distribution

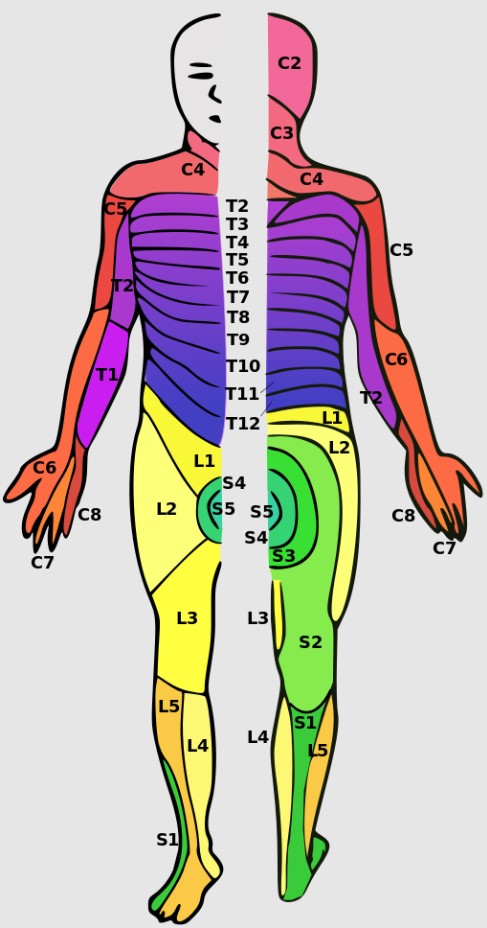

Shingles manifests as a vesicular rash. Typically, and in accordance with guidance from California Department of Public Health, a localized rash is present in one or two adjacent dermatomes and appears on either the left or right side of the body.

A dermatome is an area of skin innervated by a single cranial or spinal nerve. The number and location of dermatomes involved in the rash determine localized or disseminated infection.

Disseminated Distribution

Vesicles are considered disseminated when spread over three or more dermatomes or on both the left and right sides of the body.

2. What’s the Patient’s Immune Status?

If there is any doubt, confirm the patient’s immune status with the attending provider.

The Immunocompromised Patient

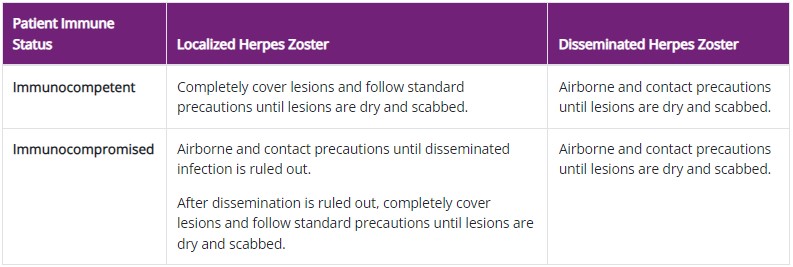

If the patient is immunocompromised and appears to have localized shingles, use Airborne and Contact precautions until dissemination is ruled out. Once ruled out, use standard precautions and cover vesicles until they dry and scab.

In the case of immunocompromise and disseminated shingles, the patient remains in Airborne and Contact precautions until vesicles dry and scab.

The Immunocompetent Patient

For the immunocompetent patient with localized shingles, use standard precautions and cover vesicles until they dry and scab.

If the immunocompetent patient has disseminated shingles, place the patient in Airborne and Contact precautions until vesicles dry and scab.

Did you notice the pattern?

This table sums it up nicely.

Call to Action

Know the Two Questions To Ask

The patient’s immune status and the dermatomal distribution of their rash will guide isolation precautions.

Outside of an oncology unit, most of your patients with shingles will not require any transmission-based precautions. Observing standard precautions and covering the vesicles is all you’ll need to do.

But remember, as standard precautions dictate, use appropriate PPE whenever there is a chance of direct contact with or aerosolization of vesicular fluid. The fluid is infectious and unprotected exposure to the fluid can transmit VZV to a non-immune person.