CHG: Mechanism of Action and Limitations of Use

Being hospitalized can be a scary event for many reasons. Getting a healthcare-associated infection (HAI) is just one reason.

One in 31 patients has at least one HAI during their hospitalization.

Infections can lead to sepsis and even death. At best, infections require exposure to antibiotics.

And while antibiotics can be lifesaving, they come with their own slew of down sides.

Chlorhexidine gluconate (CHG) is one of healthcare’s most widely used weapons in the fight against HAIs.

CHG is a broad-spectrum antiseptic that continues to work long after it is applied. For decades, evidence of CHG’s ability to reduce bioburden, HAIs, and in some cases disrupt biofilm, has made it a go-to antiseptic.

If you’ve ever wondered how CHG works as an biocide or what some of its limitations are, read on. This article describes the basic mechanism behind CHG’s antimicrobial action and describes limitations you’re likely to come across in clinical practice.

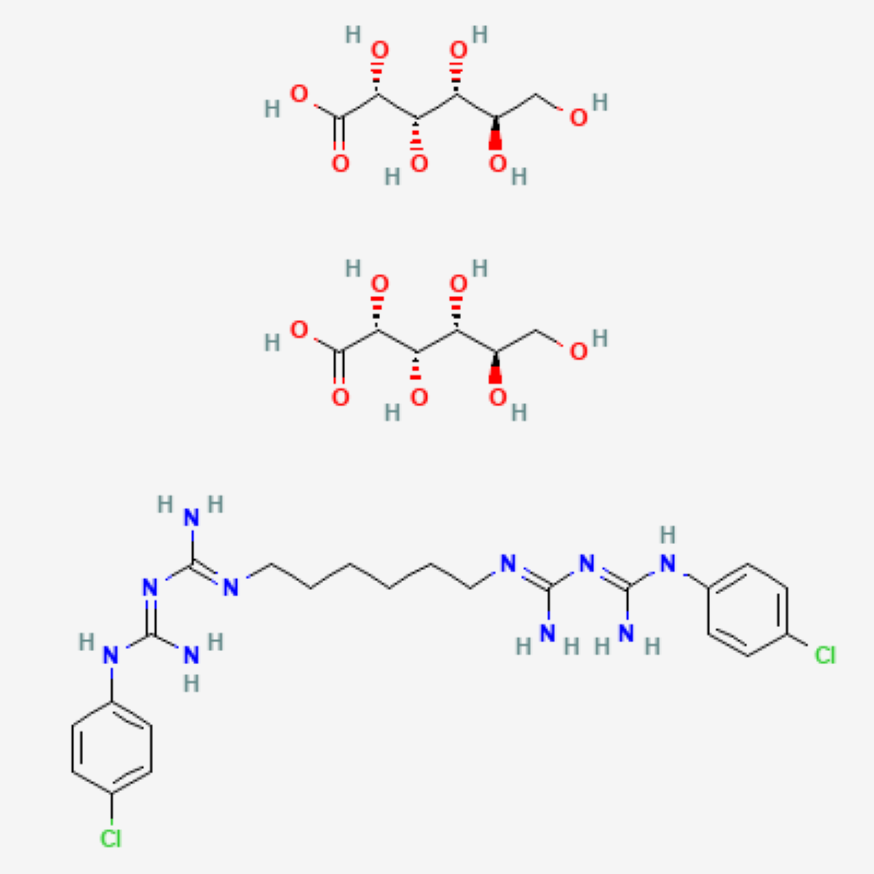

CHG Is a Cationic Surfactant

First, we need to talk a little chemistry.

Surfactants are chemical compounds that form micelles around dirt and microorganisms on surfaces, for example, skin. Micelles separate dirt and microorganisms from their surface (skin).

It’s how soap, shampoo and laundry detergents work, too.

In liquid form, CHG is a cationic surfactant meaning it is a positively charged surfactant. CHG binds to the negative charges found on bacterial cell walls.

The CHG-cell wall binding breaks the cell wall causing leakage of potassium ions and protons from the cell. And this is at low concentrations! At higher concentrations, CHG ravages the cell, breaking open the organism’s cytoplasmic membrane.

The microbe is unable to function and is killed.

CHG also binds to select proteins of the stratum corneum layer of skin and remains active for hours after application. Use CHG-compatible soaps and lotions if your patient is receiving a CHG bath so you don’t deactivate the CHG.

CHG Has Its Limitations

CHG has been used in healthcare since the 1950s. It’s efficacious and low-toxic. And despite being one of the most widely used antiseptics in healthcare, it’s “not a panacea.”

You should be aware of some limitations:

- Soaps, body washes and lotions containing anionic ingredients will deactivate CHG.

- Use CHG-compatible cleansers and lotions if your patient is receiving a CHG bath.

- CHG is non-sporicidal.

- Soap and water bathing is recommended for your C. diff patients.

- CHG can irritate the skin.

- Irritation can occur if a skin-prep is not allowed to completely air dry before applying a transparent dressing. I’ve seen this many times under PICC or hemodialysis catheter dressings.

- Some microbial resistance has been documented.

Call to Action

Now you are familiar with how CHG works and aware of some of its limitations.

Use this information to educate your peers.

Use this information to educate your patients when they ask you why they need a CHG bath instead of a soap and water bath or why they must use a CHG-compatible lotion.

And equally importantly, use this information to feel more confident when using CHG.